When a healthcare provider suggests genetic testing for a personal or family history of breast cancer, they may say “BRCA testing.” However, this term doesn’t capture the full scope of what geneticInherited characteristics. testing offers today.

The first BRCA tests, introduced in 1996, were groundbreaking but had limitations. Early testing technology often missed certain BRCA mutations, leaving gaps in the results. Over the past three decades, genetic testing has evolved significantly. Today’s tests not only detect a wider range of BRCA mutations but also screen for variations in many other genes linked to breast cancer risk.

If you underwent genetic testing before 2012, your analysis may not have been as comprehensive as it could be today. Consulting with a genetics professional can help you determine whether updated testing is recommended, ensuring you have the most accurate and complete information about your genetic risk.

Multi-Gene Panel Testing: What Does it Look For?

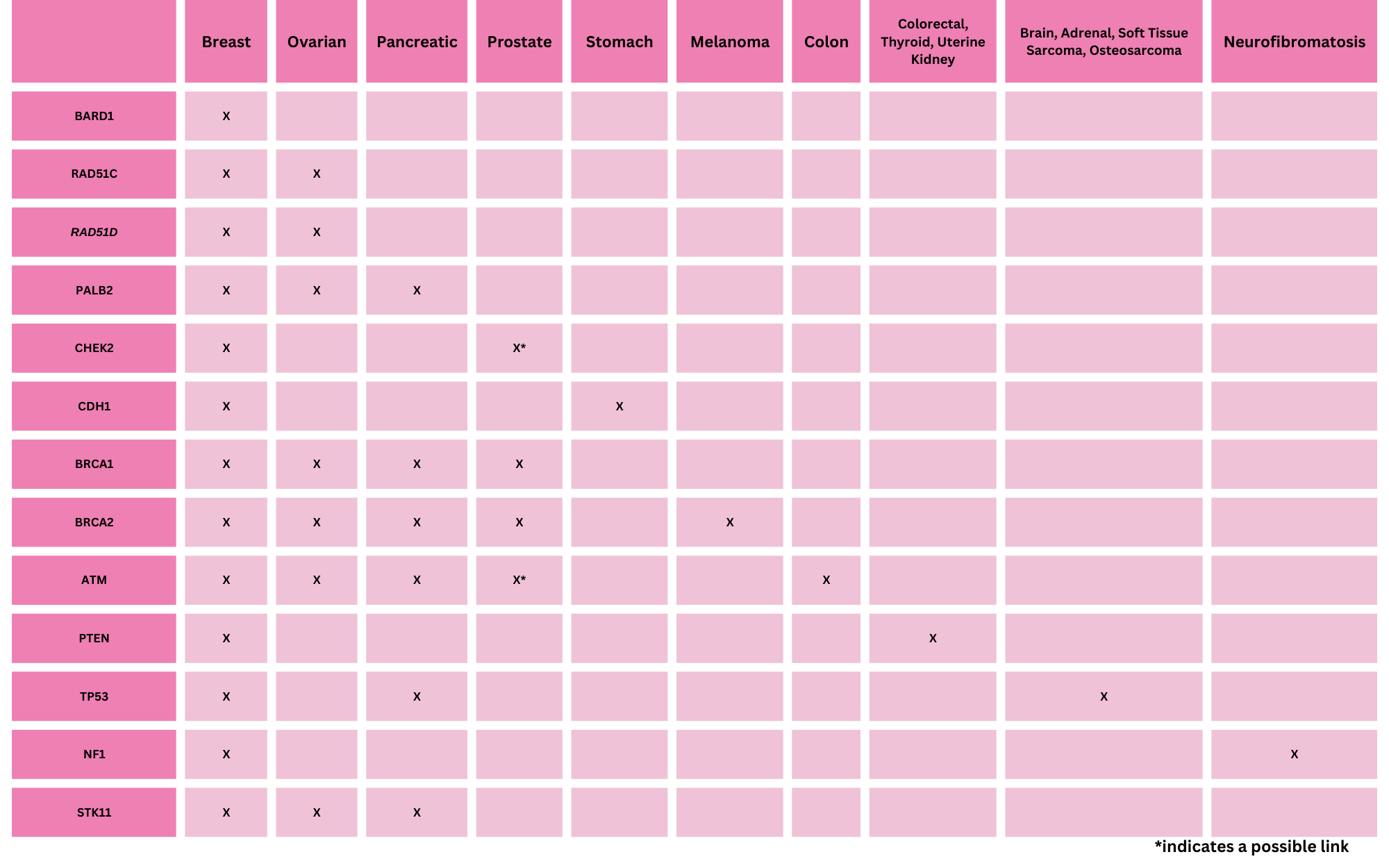

Current genetic tests are not only more accurate, research has identified multiple genes associated with hereditary breast cancer. Current testing with a “hereditary breast cancer multi-gene panel” includes at least eight genes. Most of these newer genes are associated with other cancers in addition to breast cancer. The table below lists the type of cancer along with the genes associated with them:

Risk Levels and Screening Recommendations

While all 13 genes have mutations that are associated with a risk of breast cancer that is higher than the general population risk of 12%, the gene-specific breast cancer risks vary widely, from 17% to greater than 60%.

- “High-risk” genes (e.g., BRCA1A gene which, when damaged or mutated, can put a person at a greater risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer., BRCA2A gene which, when damaged or mutated, may put a woman at a greater risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer. This gene is also thought to raise the risk for breast cancer in men., CDH1, PALB2, STK11, TP53) are associated with a lifetime breast cancer risk of around 40% or more.

- “Moderate-risk” genes (e.g., ATM, BARD1, CHEK2, NF1, RAD51C, RAD51D) are linked to breast cancer risk lower than 40%.

Because different genes have different cancer risks, recommendations regarding screening and surgery differ depending on the specific genetic mutation.

The risks associated with a particular geneA sequence in the DNA which can be passed down from parent to child. Genes helps determine physical and functional traits for the body. can change as more information is collected and more comprehensive studies are published. Until recently, the breast cancer risk quoted for a CHEK2 mutation was 20-40%, along with an increased risk of colon cancer. More recent studies of CHEK2 indicate a lower risk of breast cancer (23-27%) and a risk of colon cancer that is not significantly higher than that of the general population.

Additionally, there are genes previously associated with breast cancer for which there is currently insufficient evidence that mutations in these genes actually increase the risk of breast cancer. While the following genes are still found on some breast cancer multi-gene panels, changes in medical management are not suggested when mutations are detected: FANCC, MRE11, NBN, RAD50, RECQL, and XRCC2.

Are Most Breast Cancer Cases Hereditary?

It’s important to remember that cancer is usually sporadic and random, not hereditary. Most cancer is due to a combination of aging, diet, lifestyle and environment, rather than an inherited mutation. The majority of people having genetic testing will receive results that are negative, or normal. Hereditary cancer syndromes account for approximately 10% of cancer overall. Features of hereditary cancer are:

- Diagnosis before age 50

- BilateralOn both sides. or multiple primary cancers

- Multiple affected relatives on one side of the family and in multiple generations

Increased screening for breast cancer may be recommended even when genetic testing is negative. Despite advances in genetic testing, there may still be cancer-related mutations that cannot be detected with current technology. Also, families share genes, but they may also share the other risk factorsAnything that increases or decreases a person’s chance of developing a disease. for cancer (diet, lifestyle and environment). Considering unknown genetic factors, and shared familial environments, women who have a first-degree relative with breast cancer have a risk themselves that is approximately double the general population. Therefore, even if genetic testing is negative for breast cancer-related genetic mutations, a higher level of screening may be recommended based on family history.